An infinite non-cyclic group whose proper subgroups are cyclic

The Fall semester of 2013 just ended and one of the classes I taught was abstract algebra. The course is intended to be an introduction to groups and rings, although, I spent a lot more time discussing group theory than the latter. A few weeks into the semester, the students were asked to prove the following theorem.

The Fall semester of 2013 just ended and one of the classes I taught was abstract algebra. The course is intended to be an introduction to groups and rings, although, I spent a lot more time discussing group theory than the latter. A few weeks into the semester, the students were asked to prove the following theorem.

Theorem. If $G$ is a cyclic group, then all the subgroups of $G$ are cyclic.

As with all conditional theorems, I also encouraged my students to think about whether the converse of this theorem is true. That is, if all the subgroups of a group $G$ are cyclic, does this imply that $G$ is cyclic? Well, since $G$ is always a subgroup of itself, the answer is clearly yes. But this isn’t the interesting question to ask. Instead, we should ask:

If $G$ is a group such that all proper subgroups are cyclic, does this imply that $G$ is cyclic?

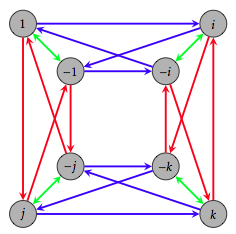

The answer is “no” and my students were able to quickly come up with a few counterexamples. In particular, they mentioned the dihedral group $D_3$ (symmetry group for an equilateral triangle), the Klein four-group $V_4$, and the Quarternion group $Q_8$. The groups $D_3$ and $Q_8$ are both non-abelian and hence non-cyclic, but each have 5 subgroups, all of which are cyclic. The group $V_4$ happens to be abelian, but is non-cyclic. Yet it has 4 subgroups, all of which are cyclic.

Following the discussion of these three examples, one of my students asked whether the question above is true for infinite groups. I responded with something like, “Uh…well…no, I don’t think so. Hmmm, let me think about it.” So, I thought about it off and on for a couple hours, but didn’t make much headway. I decided to roam the hallways and recruit some help. I ended up chatting with my colleagues Mike Falk, Jim Swift, and Jeff Rushall. Collectively, we all thought about it a little bit here and a little bit there. I was fairly confident that an internet search would provide some insight, but I was intentionally putting that off in the hopes that I could come up with an example.

A couple days later, I was meeting with one of my undergraduate research students and we chatted briefly about the problem. A few hours after we met, he sent me a link to a discussion on Math Stack Exchange, which contains a response that is precisely about the question above.

Without further ado, here’s an example that confirms that the answer to the question above is “no” even if the group is infinite.

Theorem. Let $p$ be a prime. Then the Prüfer $p$-group $\mathbb{Z}(p^{\infty})=\{z\in\mathbb{C}\mid z^{p^n}=1, n\in\mathbb{Z}^+ \}$ is an infinite abelian non-cyclic group whose proper subgroups are cyclic.

In fact, all proper subgroups of $\mathbb{Z}(p^{\infty})$ are finite! Cool.

Dana C. Ernst

Mathematics & Teaching

Northern Arizona University

Flagstaff, AZ

Website

928.523.6852

BlueSky

Instagram

Facebook

Strava

GitHub

arXiv

ResearchGate

LinkedIn

Mendeley

Google Scholar

Impact Story

ORCID

Buy me a coffee

Current Courses

About This Site

This website was created using GitHub Pages and Jekyll together with Twitter Bootstrap.

Unless stated otherwise, content on this site is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License.

The views expressed on this site are my own and are not necessarily shared by my employer Northern Arizona University.

The source code is on GitHub.

Land Acknowledgement

Flagstaff and NAU sit at the base of the San Francisco Peaks, on homelands sacred to Native Americans throughout the region. The Peaks, which includes Humphreys Peak (12,633 feet), the highest point in Arizona, have religious significance to several Native American tribes. In particular, the Peaks form the Diné (Navajo) sacred mountain of the west, called Dook'o'oosłííd, which means "the summit that never melts". The Hopi name for the Peaks is Nuva'tukya'ovi, which translates to "place-of-snow-on-the-very-top". The land in the area surrounding Flagstaff is the ancestral homeland of the Hopi, Ndee/Nnēē (Western Apache), Yavapai, A:shiwi (Zuni Pueblo), and Diné (Navajo). We honor their past, present, and future generations, who have lived here for millennia and will forever call this place home.