An Iterated Prisoner's Dilemma (Talk)

On Thursday, October 17, I gave an hour long talk in our department seminar titled “An Iterated Prisoner’s Dilemma.” There were about 35 people in attendance, including undergraduates (mostly my calculus students), graduate students, and faculty from the Mathematics & Statistics Department at Northern Arizona University. I was pleased with the turnout since our seminars are usually on Tuesdays and I wasn’t sure how many people would come on a non-standard day. Here is the abstract for the talk:

The Prisoner’s Dilemma goes something like this. Two members of a criminal gang are arrested and imprisoned. Each prisoner is in solitary confinement with no means of speaking to or exchanging messages with the other. The police admit they don’t have enough evidence to convict the pair on the principal charge. They plan to sentence both to a year in prison on a lesser charge. Simultaneously, the police offer each prisoner a bargain. If A and B both confess the crime, each of them serves 2 years in prison. If A confesses but B denies the crime, A will be set free whereas B will serve 3 years in prison (and vice versa). If A and B both deny the crime, both of them will only serve 1 year in prison. In this talk, we will first discuss this classic game theoretic problem and then introduce an iterative version that consists of a round robin tournament of teams, where the winner is the team that spends the least amount of time in prison.

I pretty much lifted this straight from the Wikipedia page on the Prisoner’s Dilemma. So, thanks to the author(s) of that page!

There were several motivating factors in choosing this topic. First, every once in a while, I like to give a talk about something that I don’t know much about. Doing this forces me to learn something new. Also, I’ve found that some of my best talks are on things that I am not an expert on. Certainly, one of the reasons why this is true is that I’m likely to pitch a talk at a lower level if I’m talking about something unfamiliar. I don’t know about you, but I much prefer sitting through a talk when I understand most of what’s going on. Culturally, it seems acceptable to give talks where most of the audience doesn’t understand most of the talk. I’m trying to give talks where this doesn’t happen.

It’s expected that our graduate students (we have a masters program at NAU) attend our weekly seminars, but lately their attendance has been poor. I wanted to pick a topic that might entice them to start coming.

I ended up choosing the Prisoner’s Dilemma as a topic because I wanted to learn more about game theory and I figured the topic would be accessible. Moreover, I was inspired by Google+ and blog posts by Vincent Knight and Paul Harper (both from Cardiff University). There was also an excellent Radiolab episode about the Prisoner’s Dilemma back in 2010 that planted a seed for me. I’d like to thank Vince and Paul for helping out while I was preparing my talk. In particular, my slides are a modification of Vince’s slides, which he discusses here.

Without further ado, the slides for my talk are available here.

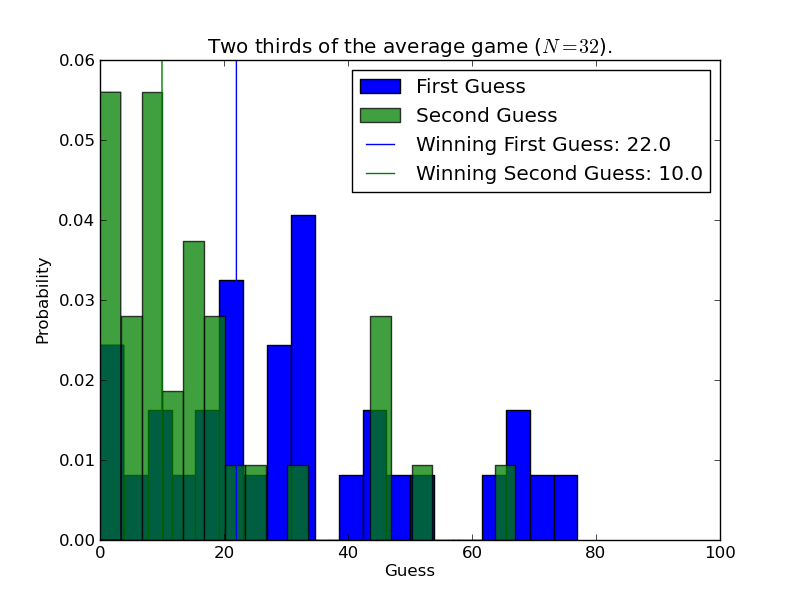

As you can see by looking at the slides, the talk began with an activity involving the Two Thirds of Average Game. During the activity, the audience made two different guesses. While I was giving the rest of the talk, I had a volunteer enter all the guesses into a csv file on the Sagemath Cloud. At the end of the talk, I ran Vince’s python script on the csv file in the Sagemath cloud. The output told me who the winners were for both rounds of guessing and provided a dandy looking graph, seen below.

I provided the winners with some chocolate.

Around slide 18, the plan was to conduct an Iterated Prisoner’s Dilemma tournament involving 4 teams, but I was a little worried about running out of time. So, I decided to wait until the end of the talk and do it if I had time. I ended up squeezing in a 3-team tournament that we probably flew through too quickly to get much out of, but it was fun nonetheless. The three team names were the United States, North Korea, and Russia. North Korea ended up winning, but only by a small margin.

Dana C. Ernst

Mathematics & Teaching

Northern Arizona University

Flagstaff, AZ

Website

928.523.6852

Instagram

Strava

GitHub

arXiv

ResearchGate

LinkedIn

Mendeley

Google Scholar

Impact Story

ORCID

About This Site

This website was created using GitHub Pages and Jekyll together with Twitter Bootstrap.

Unless stated otherwise, content on this site is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License.

The views expressed on this site are my own and are not necessarily shared by my employer Northern Arizona University.

The source code is on GitHub.

Land Acknowledgement

Flagstaff and NAU sit at the base of the San Francisco Peaks, on homelands sacred to Native Americans throughout the region. The Peaks, which includes Humphreys Peak (12,633 feet), the highest point in Arizona, have religious significance to several Native American tribes. In particular, the Peaks form the Diné (Navajo) sacred mountain of the west, called Dook'o'oosłííd, which means "the summit that never melts". The Hopi name for the Peaks is Nuva'tukya'ovi, which translates to "place-of-snow-on-the-very-top". The land in the area surrounding Flagstaff is the ancestral homeland of the Hopi, Ndee/Nnēē (Western Apache), Yavapai, A:shiwi (Zuni Pueblo), and Diné (Navajo). We honor their past, present, and future generations, who have lived here for millennia and will forever call this place home.