Foundations of Mathematics

Welcome

Welcome to the course web page for the Spring 2020 manifestation of MAT 320: Foundations of Mathematics at Northern Arizona University.

Course Info

Title: MAT 320: Foundations of MathematicsSemester: Spring 2020

Credits: 3

Section: 2

Time: 12:40-1:30PM MWF

Location: AMB 163

Instructor Info

Dana C. Ernst, PhDAMB 176

9:00-10:00AM MWF, 9:00-11:00AM T

dana.ernst@nau.edu

928.523.6852

danaernst.com

What is This Course All About?

The primary objective of this course is to develop skills necessary for effective proof writing. Students will improve their ability to read and write mathematics. Successful completion of MAT 320 provides students with the background necessary for upper division mathematics courses. Also, the purpose of any mathematics course is to challenge and train the mind. Learning mathematics enhances critical thinking and problem solving skills. The course description says:

The course trains students on methods and techniques of mathematical communication, focusing on proofs but also covering expository writing and problem-solving explanations.

This course will likely be different than any other math class that you have taken before for two main reasons. First, you are used to being asked to do things like: “solve for $x$,” “take the derivative of this function,” “integrate this function,” etc. Accomplishing tasks like these usually amounts to mimicking examples that you have seen in class or in your textbook. The steps you take to “solve” problems like these are always justified by mathematical facts (theorems), but rarely are you paying explicit attention to when you are actually using these facts. Furthermore, justifying (i.e., proving) the mathematical facts you use may have been omitted by the instructor. And, even if the instructor did prove a given theorem, you may not have taken the time or have been able to digest the content of the proof.

Unlike previous courses, this course is all about “proof.” Mathematicians are in the business of proving theorems and this is exactly our endeavor. For the first time, you will be exposed to what “doing” mathematics is really all about. This will most likely be a shock to your system. Considering the number of math courses that you have taken before you arrived here, one would think that you have some idea what mathematics is all about. You must be prepared to modify your paradigm. The second reason why this course will be different for you is that the method by which the class will run and the expectations I have of you will be different. In a typical course, math or otherwise, you sit and listen to a lecture. (Hopefully) These lectures are polished and well-delivered. You may have often been lured into believing that the instructor has opened up your head and is pouring knowledge into it. I absolutely love lecturing and I do believe there is value in it, but I also believe that in reality most students do not learn by simply listening. You must be active in the learning you are doing. I’m sure each of you have said to yourselves, “Hmmm, I understood this concept when the professor was going over it, but now that I am alone, I am lost.” In order to promote a more active participation in your learning, we will incorporate ideas from an educational philosophy called inquiry-based learning (IBL).

The mathematician does not study pure mathematics because it is useful; he studies it because he delights in it, and he delights in it because it is beautiful.

This is not a lecture-oriented class or one in which mimicking prefabricated examples will lead you to success. You will be expected to work actively to construct your own understanding of the topics at hand, with the readily available help of me and your classmates. Many of the concepts you learn and problems you work will be new to you and ask you to stretch your thinking. You will experience frustration and failure before you experience understanding. This is part of the normal learning process. If you are doing things well, you should be confused at different points in the semester. The material is too rich for a human being to completely understand it immediately. Your viability as a professional in the modern workforce depends on your ability to embrace this learning process and make it work for you.

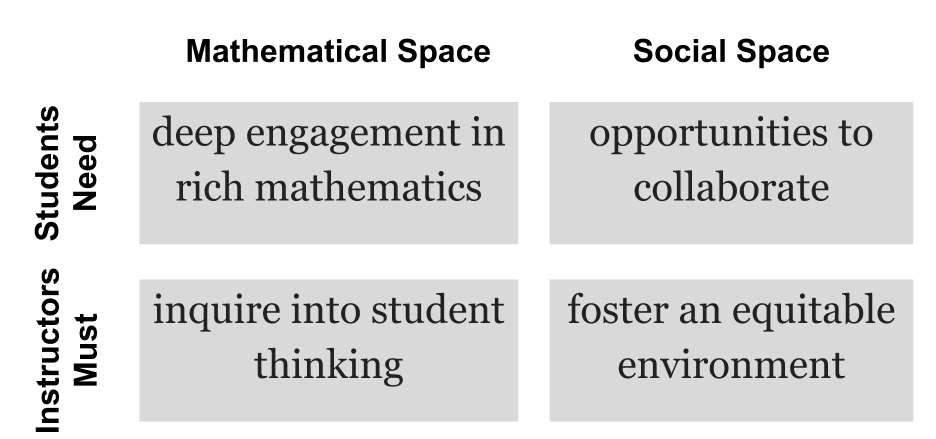

In order to promote a more active participation in your learning, we will incorporate ideas from an educational philosophy called inquiry-based learning (IBL). Loosely speaking, IBL is a student-centered method of teaching mathematics that engages students in sense-making activities. Students are given tasks requiring them to solve problems, conjecture, experiment, explore, create, and communicate. Rather than showing facts or a clear, smooth path to a solution, the instructor guides and mentors students via well-crafted problems through an adventure in mathematical discovery. According to Laursen and Rasmussen (PDF), the Four Pillars of IBL are:

- Students engage deeply with coherent \& meaningful mathematical tasks.

- Students collaboratively process mathematical ideas.

- Instructors inquire into student thinking.

- Instructors foster equity in their design and facilitation choices.

If you want to learn more about IBL, read my blog post titled What the Heck is IBL?.

Don’t fear failure. Not failure, but low aim, is the crime. In great attempts it is glorious even to fail.

Much of the course will be devoted to students presenting their proposed solutions/proofs on the board and a significant portion of your grade will be determined by how much mathematics you produce. I use the word “produce” because I believe that the best way to learn mathematics is by doing mathematics. Someone cannot master a musical instrument or a martial art by simply watching, and in a similar fashion, you cannot master mathematics by simply watching; you must do mathematics!

In any act of creation, there must be room for experimentation, and thus allowance for mistakes, even failure. A key goal of our community is that we support each other—sharpening each other’s thinking but also bolstering each other’s confidence—so that we can make failure a productive experience. Mistakes are inevitable, and they should not be an obstacle to further progress. It’s normal to struggle and be confused as you work through new material. Accepting that means you can keep working even while feeling stuck, until you overcome and reach even greater accomplishments.

You will become clever through your mistakes.

Furthermore, it is important to understand that solving genuine problems is difficult and takes time. You shouldn’t expect to complete each problem in 10 minutes or less. Sometimes, you might have to stare at the problem for an hour before even understanding how to get started. In fact, solving difficult problems can be a lot like the clip from The Big Bang Theory located here.

In this course, everyone will be required to

- read and interact with course notes and textbook on your own;

- write up quality solutions/proofs to assigned problems;

- present solutions/proofs on the board to the rest of the class;

- participate in discussions centered around a student’s presented solution/proof;

- call upon your own prodigious mental faculties to respond in flexible, thoughtful, and creative ways to problems that may seem unfamiliar at first glance.

As the semester progresses, it should become clear to you what the expectations are.

Tell me and I forget, teach me and I may remember, involve me and I learn.

Dana C. Ernst

Mathematics & Teaching

Northern Arizona University

Flagstaff, AZ

Website

928.523.6852

Instagram

Strava

GitHub

arXiv

ResearchGate

LinkedIn

Mendeley

Google Scholar

Impact Story

ORCID

About This Site

This website was created using GitHub Pages and Jekyll together with Twitter Bootstrap.

Unless stated otherwise, content on this site is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License.

The views expressed on this site are my own and are not necessarily shared by my employer Northern Arizona University.

The source code is on GitHub.

Land Acknowledgement

Flagstaff and NAU sit at the base of the San Francisco Peaks, on homelands sacred to Native Americans throughout the region. The Peaks, which includes Humphreys Peak (12,633 feet), the highest point in Arizona, have religious significance to several Native American tribes. In particular, the Peaks form the Diné (Navajo) sacred mountain of the west, called Dook'o'oosłííd, which means "the summit that never melts". The Hopi name for the Peaks is Nuva'tukya'ovi, which translates to "place-of-snow-on-the-very-top". The land in the area surrounding Flagstaff is the ancestral homeland of the Hopi, Ndee/Nnēē (Western Apache), Yavapai, A:shiwi (Zuni Pueblo), and Diné (Navajo). We honor their past, present, and future generations, who have lived here for millennia and will forever call this place home.